Just as Early Learning Nation showcases the ways families, researchers and grassroots nonprofits and organizations are building an early learning nation—one community at a time—our Community Cultivators series highlights how innovators across all sectors build and sustain global communities from the ground up. We hope the series inspires your own early childhood work.

A decade ago, early childhood advocacy could be a lonely pursuit. “It felt like we were talking to an empty auditorium,” says Bruce D. Perry, MD, Ph.D. “Now there are more people in the auditorium. They’re recognizing the power of early childhood, the importance of creating policy and practice that will benefit children and that will meet the needs of the adults who are caring for young children.”

Perry is best known as the co-author, with Oprah Winfrey, of the bestselling What Happened to You?: Conversations on Trauma, Resilience and Healing (2021). The book, however, is just one highlight of a 30+-year career as teacher, clinician and researcher in neuroscience and children’s mental health. His research and clinical experience show the importance of the first years—and in particular, the first few months—and he has been a steadfast champion of early education.

“Perry’s work,” says Dr. Kristie Brandt, director of the University of California Davis Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship, “has advanced the early childhood field to new levels. He has revolutionized our understanding of the importance of the first months, without adopting a fatalist position in the event of early trauma. He champions truly personalized care with greater potential for helping and healing.”

After seeing him deliver a powerful keynote address at a Children’s Movement of Florida webinar this past October, I sought him out to probe his views further and to find out more about the Neurosequential Network—the virtual community he founded.

👉 5 Top Takeaways from the Children’s Movement of Florida’s Born to Thrive Annual Summit

1. Human beings are born curious. Children and other members of our species want to explore the world, and exploration gives us great pleasure. Perry, who grew up in North Dakota, credits his family for his own lifelong appetite for acquiring knowledge. “My dad and mom were both really curious people,” he recalls. “Both read a lot, and my brother taught me a lot about animal behavior when we went hunting and fishing. He knew the birds of our neighborhood and showed me how to be quiet and observe. So, I learned about the predictability inherent in biological systems, that if you observe them and take enough time, things that seemed completely random really made complete sense.”

Basic child development tells us that if children feel safe, they go explore the world and then come back to the parent or caregiver to get regulated, and then go explore again. When the adults in a child’s life nurture this tendency, as the child grows up, it can blossom into a willingness to travel, to learn new languages, to sample different foods and so on. Curiosity about other humans, Perry says, is a powerful antidote to the fearfulness poisoning society. “When we’re curious,” he says, “we become more accepting and aware of the power of diversity.” Diversity a sign of health in any biological system, he stresses.

2. Human beings are healthiest in community. Perry harks back to early human society, when we lived in clans of 80 or so. Evolutionarily speaking, this is the optimal number of close relationships for brain development, and the health of the community, then and now, largely determines the health of the individual. “Human beings are really such social creatures,” he says, “that the most meaningful way to look at and solve problems really is on a systemic basis.” In contrast, the way society is currently constructed, we tend to focus on people as individuals, resulting in “well-intended efforts that fail.”

The child care workforce is a case in point. Citing the widespread burnout in the field, Perry says, the default assumption is to promote self-care. “Yet that only gets you so far,” warns Perry. “Early Care providers could have the best self-care model in the world, but if every day you go into a system that grinds you down, doesn’t pay a fair wage, uses ratios that make it hard to meet the developmental needs of each child, it just isn't going to work. We have to approach these problems in a different way, taking into account the relationship between economic policy and early childhood, as well as the relationship between historical structures that are inherently racist and the impact that has on physical health.”

Shifting the culture so that early educators feel valued is a project that will take years. To that end, the Neurosequential Network comprises organizations and individuals—including educators, parents, policymakers, social workers and students (including middle and high schoolers)—who study neurodevelopment and make use of the latest research. “We try to operationalize these concepts,” he says. “And we've been pleasantly surprised at how many people have found this to be a powerful way to understand issues.” The network operates in more than 30 countries and includes several hundred thousand people.

3. Stress changes the biology of the brain. In 1973, during his freshman year at Stanford University, Perry enrolled in a seminar taught by Seymour Levine, a pioneer of research into stress hormones. Epigenetics, defined by the CDC as “the study of how your behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way your genes work,” was still in its infancy (so to speak). He recalls being struck by the fact that a very brief experience on day three of a rat’s life could have a lifelong impact. “From that point forward,” he says, “I was studying it one way or another.”

Thanks to the popularity of books like What Happened to You? and Bessel van der Kolk’s The Body Keeps the Score, post-traumatic stress disorder is a commonly understood phenomenon, but Perry notes that 30 years ago, even many clinicians in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, along with many other leading institutions, failed to recognize it as a legitimate diagnosis. “The field is evolving,” he remarks, “so I'm hopeful about that.”

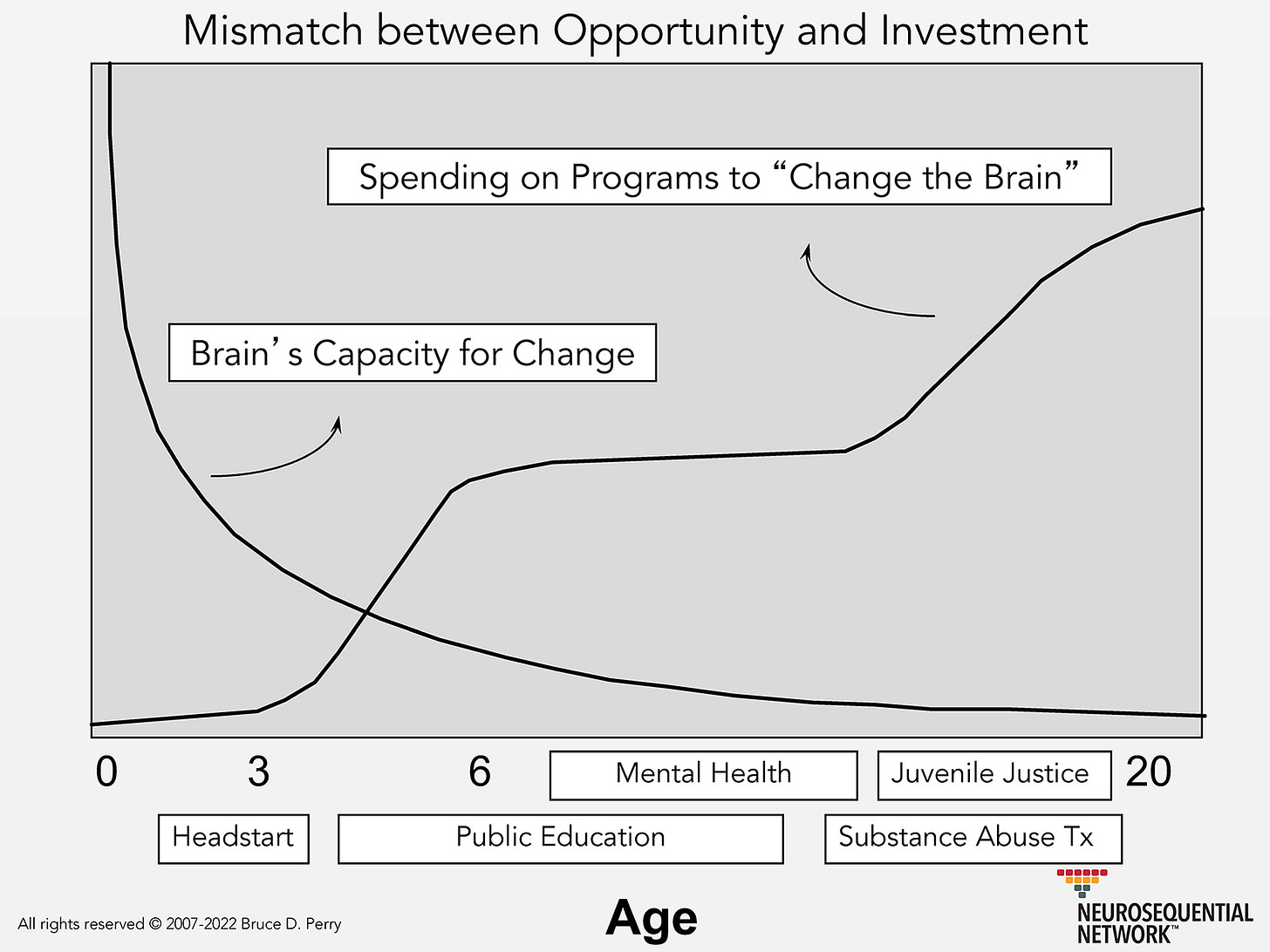

Although science has repeatedly confirmed the importance of early brain development across species, Perry remains amazed by the simple fact that if children are safe and regulated during their first couple months, it acts as a kind of inoculation against bad things happening later in life. On the other hand, those whose lives start out rough but then have consistent, predictable, nurturing experiences—they tend to struggle. “It’s one of those things that clinicians see every day,” Perry says, “and it has such powerful implications for policy. It's such a logical place for us to put a lot of our attention and efforts. It just makes sense to take care of the adults who work with young kids. We just have not done it very well.”

A father of five and grandfather of four, Perry reflects that he was lucky to have become a parent before he became a clinician. “My kids taught me a lot more about development than my formal training did,” he acknowledges.

4. Touch is good for the brain. The fancy term is the somatosensory system, defined by the National Institutes of Health as the “network of neurons that help humans recognize objects, discriminate textures, generate sensory-motor feedback and exchange social cues.” Nonsexual hugging and touching are natural and physiologically healthy, Perry contends. “Toddlers need to be held. They like to be rocked. They like to push. They like that heavy press of a hug.”

In What Happened to You? “touch-starved” is the haunting term he uses to describe many children in our society. Whether it’s an over-reliance on screens and technology or misguided prohibitions against any physical contact with students, American society is betraying our own somatosensory systems.

“We need to figure out our relationship with touch in our society,” Perry says. We need to figure out ways to incorporate it more.”

5. ‘Resilience’ is misunderstood. Because resilience is such an incredibly powerful concept, it’s important that we comprehend what it is—and what it isn’t. As he clarifies in What Happened to You?: “We often use our belief in another person’s ‘resilience’ as an emotional shield…. We see the same rationalization and avoidance in the face of large-scale or community trauma—war, famine, natural disasters, school shootings, the transgenerational impact of slavery.”

Relying on resilience as a silver bullet, Perry, worries, leads to schools in high-poverty neighborhoods to declare that it’s focusing on this magical quality and then to assign a book on the subject or hold a webinar without taking the necessary steps to address the underlying socioeconomic issues. “It's a weird form of toxic positivity,” he says.

“Real resilience,” explains Perry, “is built from stress, but it has to be predictable, controllable stress.” He cites the example of a teacher who requires students to get up in front of class every Wednesday to recite a poem, which is different from a situation where students are episodically put on the spot and asked to do something beyond their capabilities.

The common thread of all these lessons is the need for nuance—a quality sorely lacking in many of today’s debates. “Human beings love simple, linear explanations,” Perry observes. “But development is complex. We still have a lot to learn.”

Favorite Quotes from What Happened to You? by Bruce Perry

“If we help the children but don’t meet the needs of the adults, our work will have little impact.”

“A person’s capacity to connect, to be regulating and regulated, to reward and be rewarded, is the glue that keeps families and communities together.”

“Existing child-welfare, educational, mental health and juvenile-justice systems… fragment families, undermine community, and engage in marginalizing, shaming and punitive practices.”

“We expect a single working mother to be the one to throw the baseball with her eight-year-old, rock the newborn, read to the three-year-old, and, by the way, cook a nutritious meal, help with homework, do the laundry, get everyone to bed, then wake up and get them all ready for child care and school so she can go work all day, only to rush home to do it all again. All alone…. [they] end up feeling like they are inadequate—that there is something wrong with them, that they aren’t enough. When really, it’s the modern world that’s not enough.”

“Children are not born ‘resilient,’ they are born malleable.”

“Trauma can also arise from quieter, less obvious experiences, such as humiliation or shaming or other emotional abuse by parents, or the marginalization of a minority child in a majority community.”

Early Learning Nation is an initiative of the

Bezos Family Foundation

1700 7th Ave Ste 116

Seattle, WA 98101-1323 USA